Prefilled Syringe Opener From A 3d Printer

Intravitreal injection of an anti-VEGF agent is an effective mainstay of treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration, diabetic macular edema, retinal vein occlusion, and myopic degeneration.1-5 The US FDA approved the use of a prefilled syringe (PFS) of 0.5 mg and 0.3 mg of ranibizumab (Lucentis, Genentech) in October 2016 and March 2018, respectively.5

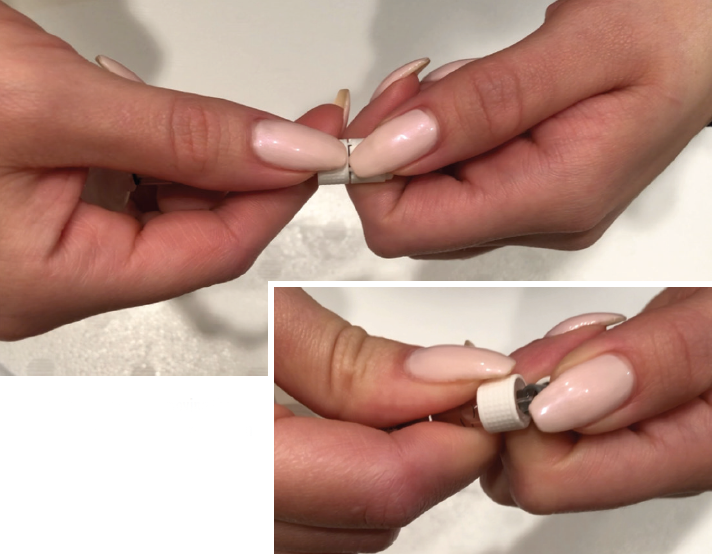

The use of a PFS has been associated with a reduced rate of endophthalmitis. It allows physicians to eliminate several steps from the preparation and administration process, including disinfecting the vial, attaching a filter needle to draw up medication, and removing this needle and replacing it with an injection needle.6 These capped syringes come filled with 0.165 mL of ranibizumab at the indicated concentration. To prepare the drug for administration, the physician or assistant snaps the cap off the syringe and attaches a sterile 30-gauge needle to administer the drug. The PFS, however, is modest in length (71.88 mm), and the cap measures 10.1 mm.5 These small sizes can make maintaining sterility difficult for individuals with large hands, gloved hands, and/or hands that have long fingernails (Figure 1).

This tool can be easily produced by any 3D printer with use of a stereolithography file containing the blueprint. Stereolithography files create an interface between computer-aided design software and a 3D printer.

The authors wish to acknowledge Mr. Steven Herman of the Germantown Academy in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, for his valuable and professional guidance during the planning and development of this project. They also wish to express appreciation for the 3D design and printing resources of the Beard Center for Innovation at the Germantown Academy.

Read the article, published in Retina Today: October 2019: The Surgery Issue

-

Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al; MARINA Study Group. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(14):1419-1431.

-

Brown DM, Michels M, Kaiser PK, et al; ANCHOR Study Group. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin photodynamic therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results of the ANCHOR study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(1):57-65.e5.

-

Campochiaro PA, Heier JS, Feiner L, et al; BRAVO Investigators. Ranibizumab for macular edema following branch retinal vein occlusion: six-month primary end point results of phase III study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1102-1112.e1.

-

Wolf S, Balciuniene VJ, Laganovska G, et al; RADIANCE Study Group. RADIANCE: a randomized controlled study of ranibizumab in patients with choroidal neovascularization secondary to pathologic myopia. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(3):682-692.e2.

-

Lucentis [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech; 2017.

-

Storey PP, Tauqeer Z, Yonekawa Y, et al; Post-Injection Endophthalmitis (PIE) Study Group. The impact of prefilled syringes on endophthalmitis following intravitreal injection of ranibizumab. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;199:200-208.

Murtaza Adam, MD

• Physician, Colorado Retina Associates, Denver

• Financial disclosure: Consultant (EyePoint Pharmaceuticals, Genentech), Speakers Bureau (Novartis, Regeneron)

Ferhina S. Ali, MD, MPH

• Vitreoretinal surgeon, Retina Center of Texas, Dallas

• Financial disclosure: Consultant Medical Director (Genentech)

Mitchell S. Fineman, MD

• Attending Surgeon, Retina Service, Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia

• Associate Professor, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia

• Financial disclosure: Research Funding (Genentech)

Nathan Wong

• Student, Franklin and Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennsylvania

• Financial disclosure: None